With the loss of Crimean Tatar statehood and the annexation of Crimea by the russian Empire in 1783, the national liberation struggle of the Crimean Tatar people began. Taking forms and methods at various stages, from an open armed uprising to cultural and educational activities, from requests addressed to the rulers to rallies and actions of disobedience, it subsided and flared up with new force. The history of the struggle for the restoration of people’s rights is marked by dramatic events and the names of national heroes who sacrificed their lives. With new strength, the national movement began to grow after the deportation in 1944.

Crimean Tatar national movement

1956–1969 years

At the beginning of the 50s of the 20th century, in the places where the Crimean Tatar people were evicted, in the republics of Central Asia, the national movement for the return to the Motherland and the restoration of their own rights became active. The foundations of the movement were laid by active representatives of the people, among whom at the beginning there were many communists, former front-line soldiers, partisans, and underground fighters. Since 1956, they have been sending appeals to Moscow addressed to the central leadership of the USSR, which were signed by thousands of Crimean Tatars. The appeals express a request to return the Crimean Tatar people to their homeland and restore the autonomous republic in Crimea. In addition to public appeals, Crimean Tatars sent individual and collective letters with similar demands to the central authorities. However, most often they remained unanswered, and the initiators of drafting the documents and the authors of the letters were persecuted. This gave rise to a petition campaign, which later spread widely and became an active form of struggle in the early stages of the movement.

Despite the first failures, the organizers of the movement do not lose heart and start work on uniting compatriots. From the fall of 1957, the first initiative groups appeared, which by the mid-1960s were already active in almost all settlements. The movement first unfolds in Uzbekistan, then in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and russia. Initiative groups were formed according to territorial characteristics: street – village (village) – city – district – oblast (regional) – republican.

Any Crimean Tatar who helped the movement in every way and made his contribution to the national cause could become an initiator (this name of the members of the initiative groups took root and was widely used among the people).

The initiative group had its core – a few people who had authority among the population. Dzheppar Akimov, Bekir Osmanov, Mustafa Selimov, Mustafa Khalilov, Amza Ablayev and others were included in the core of the Uzbekistan Republican Initiative Group – the body that actually managed the national movement. At the meetings of the initiative group, preparations for any event, event or action were discussed, representatives of the Crimean Tatar people (delegates) were elected by voting, the decisions of the Republican Council (the highest advisory body) were reported, and information was announced (underground bulletins). The initiators, in addition to collecting signatures and funds for organizing delegates’ trips to Moscow, paying lawyers who defend the Crimean Tatars in political processes, published underground literature.

The Republican Council convened monthly. The leaders of the most influential and active regional initiative groups took part in it. The council developed further strategy, tactical steps and approved the final action plan. Thus, the movement was characterized by democracy, massiveness, lack of hierarchical structure (outwardly it even looked somewhat chaotic), support and development of initiatives, semi-legal activity, loyalty to the Soviet authorities and the Communist Party, which were supposed to solve the Crimean Tatar national question.

Since 1964, the Permanent Representation of the Crimean Tatars – a delegation of people’s representatives – has been established in Moscow. The decision to send a people’s delegate belonged to the local initiative group and was approved by the republican one. The delegate was given a mandate – a document that reflected his powers and the main demands of the people. The people’s delegate leaving Moscow was replaced by another one, which made it possible to ensure the permanent presence of representatives of the Crimean Tatar people in the capital.

Here they regularly inform statesmen, heads of various scientific institutions, editorial offices of central newspapers and magazines, famous writers, scientists, and public figures about the national issue of the Crimean Tatar people. The main goal of the delegates was to gain acceptance into the leadership of the state. They succeeded in this in 1957, 1965 and 1967, when Crimean Tatar delegations were accepted at the highest state level. In addition, the delegates organized actions and rallies for various events and significant dates (usually, it was May 18 – the day of deportation and October 18 – the day of the creation of the Crimean ASSR). On such days, up to several hundred people’s delegates were in Moscow. The authorities organized raids on them throughout the city, arrested them and expelled them from the capital under supervision, sometimes equipping an entire train for this.

In 1966, the initiators independently, without state support, conducted a census of the Crimean Tatar people, as a result of which they were able to establish the real number of their people and the number of victims during Stalin’s deportation and in the first years abroad, who died on the fronts of the Second World War, heroes of the Soviet Union and medal bearers.

The years 1966–1969 were marked by the greatest activity of the Crimean Tatars. People who are opposed to the communist regime are joining the movement, they are no longer asking, but demanding to restore the rights of the Crimean Tatar people. Young people actively join the movement. New forms of struggle are emerging. Numerous meetings, demonstrations, actions dedicated to significant events are organized and held in the places of residence of the people and in Moscow. However, they are brutally opposed by the authorities

Some of the activists establish connections with the human rights movement that is emerging in the country. Through such well-known dissidents as Oleksiy Kosterin, Andriy Sakharov, Petro Grigorenko and others, the problem of the Crimean Tatar people and its National Movement is becoming known abroad. The well-known radio stations “Radio Liberty” and “Voice of America” broadcast reports on violations of the rights of the Crimean Tatars.

Under the pressure of thousands of Crimean Tatar rallies, the country’s leadership was forced on September 5, 1967 to accept the Order of the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada of the USSR, which recognized the groundlessness of the accusations against the Crimean Tatar people, but did not fully rehabilitate them. Crimean Tatars were allowed to settle all over the country, but measures were taken to prevent them from entering the Motherland in the Crimea. Despite this, hundreds of Crimean Tatar families leave for Crimea on their own, but they are not issued documents, they are not registered, adults are not hired, and children are not sent to school. Houses bought by Crimean Tatars are bulldozed by order of the authorities, families are expelled from Crimea, and the most active are arrested and sent to prison for “violation of the passport regime”.

Attempts at mass return of the people to Crimea and rapprochement with human rights defenders lead to increased repression against movement participants in all regions where Crimean Tatars live. In 1968–1969, famous activists and human rights defenders Mustafa Dzhemilev, Ilya Gabay, Petro Hryhorenko, Reshat Dzhemilev, Yuriy Osmanov, Rollan Kadiyev and many others were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment on fabricated criminal cases.

1970–1991 years

During this period, the Crimean Tatar national movement goes through stages of decline, and then a rapid increase in its activity. It acquires new organizational forms, which led to the convening of the Kurultai National Congress in 1991 and the election of a representative body at it – the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people. The main achievement of the National Movement can be considered the beginning of the mass self-return of the people to the Motherland.

In the 1970s, numerous trials and searches of activists of the National Movement, the persecution of those Crimean Tatars who returned to Crimea, differences in views on the methods of struggle and the division of currents within the movement contributed to the gradual decline of activity. It is not so often possible to collect thousands of signatures under various appeals and letters addressed to the country’s leadership. If in 1966 and 1971 the greatest number of signatures were collected under popular appeals to the regular congresses of the Communist Party – 130,000 and 60,000 respectively, then 20,000 were already under appeals to the 25th Congress in 1975, and under the appeal to Brezhnev in 1977 and the All-People’s Protest of 1979 managed to collect 4,000 signatures each. Rallies and gatherings now take place before the most important dates and gather not so many participants.

Despite the unsuccessful attempts of hundreds of Crimean Tatar families to self-return to Crimea, initiative groups continued to focus their activities on organizing the return of the people. In 1971, the initiators of the Tashkent region conducted a survey among the Crimean Tatars about their attitude to the return to the Crimea. Out of 18,000 adults surveyed, only 11 people refrained from answering and 9 spoke against returning. In the same year, after the publication of the results of another all-Union census, not finding Crimean Tatars in the list of nations of the USSR, initiative groups conducted a census of compatriots in all their places of residence on their own.

Despite the unsuccessful attempts of hundreds of Crimean Tatar families to self-return to Crimea, initiative groups continued to focus their activities on organizing the return of the people. In 1971, the initiators of the Tashkent region conducted a survey among the Crimean Tatars about their attitude to the return to the Crimea. Out of 18,000 adults surveyed, only 11 people refrained from answering and 9 spoke against returning. In the same year, after the publication of the results of another all-Union census, not finding Crimean Tatars in the list of nations of the USSR, initiative groups conducted a census of compatriots in all their places of residence on their own.

In the 1970s and 1980s, trials took place and many active members of the National Movement were convicted (some again), including Jeppar Akimov, Mustafa Dzhemilev, Yuriy Osmanov, Rolan Kadiyev, Ayshe Seitmuratova, and Reshat Dzhemilev.

The authorities took various measures to prevent the active return of Crimean Tatars to Crimea. Special resolutions and decrees were adopted to strengthen the passport regime in Crimea and neighboring regions, where Crimean Tatar families often settled after unsuccessful attempts to settle in the Motherland.

Such actions of the authorities had tragic consequences. On October 19, 1968, 35-year-old Fevzi Seydaliev, who protested on Red Square in Moscow against the expulsion of his family from Crimea, was killed in prison. On June 23, 1968, 46-year-old Musa Mamut committed self-immolation in protest against the repeated eviction of his family from Crimea. On November 19, 1978, Izzet Memedulayev, who came to Crimea with his wife and three daughters, hanged himself after provocation by the local KGB branch. He was unable to formalize the purchase of the house and lived under the threat of prosecution, like many of his compatriots.

On October 15, 1978, the Soviet government adopted Resolution No. 700 “On additional measures to strengthen the passport regime in the Crimea region”, which simplified the procedure for evicting Crimean Tatars from Crimea. Hundreds of people’s representatives went to Moscow with the demand to stop the persecution of the Crimean Tatars in the Motherland. They also sought an answer to L. Brezhnev’s Cassation Statement, which demanded the annulment of all legislative acts issued from 1944 to 1976, which grossly violate the rights of the Crimean Tatar people.

In 1977, a meeting of representatives of initiative groups was held in Uzbekistan, which decided to build their further activities on the basis of this statement, and in November 1979, this decision was confirmed by another meeting of movement activists. A campaign was launched to collect signatures for collective letters and telegrams addressed to the country’s leadership.

Twice, in 1974 and 1978, the authorities made unsuccessful attempts to “root” the Crimean Tatar people in the places of exile, organizing “autonomy” for this purpose on the territory of Uzbekistan and appointing individual Crimean Tatars to leadership positions. But the Crimean Tatar people, ignoring such autonomy, continued to aspire to return to Crimea.

From the second half of the 1980s, when the process of democratization of the country began, a sharp rise of the National Movement of the Crimean Tatars began.

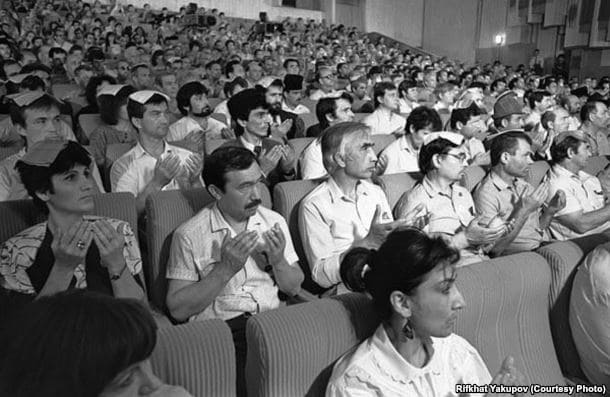

On April 11-12, 1987, the First All-Union Meeting of Initiative Group Representatives was held in Tashkent, where people’s representatives from all over Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, russia and Crimea gathered. At this meeting, it was decided to send a delegation of Crimean Tatars to the new leadership of the state to consider their national issue. The text of the nationwide appeal to M. Gorbachev was approved, under which about 40,000 signatures were collected in a short period of time. Since there was no response to this appeal, at the next All-Union meeting in Tashkent, held on June 13-14, 1987, a decision was made to hold a large peaceful demonstration in Moscow in order to draw the attention of the country’s leadership and the public to the Crimean Tatar problem. The meeting elected the Central Initiative Group (CIG) consisting of 15 people.

According to the decision of the Central Committee of the Crimean Tatar People’s Committee, it was organized to send people’s representatives to Moscow to conduct peaceful actions. On July 6 and 23, 1987, on Red Square, hundreds of Crimean Tatars held demonstrations in defense of their rights, demanding that the leaders of the state accept a delegation of people’s delegates. In response, the Moscow militia, with “special powers” granted to it to restore order in the capital, detained and expelled Crimean Tatars from Moscow.

Protest actions swept through all places where Crimean Tatars live in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, the Krasnodar region of russia, and Crimea. Peaceful demonstrations were dispersed by police units that used force against the demonstrators.

On October 7, 1987, a foot march of 2,000 Crimean Tatars set off from the city of Taman, Krasnodar Krai, to Simferopol. But at the 7th kilometer from Taman, the peaceful march was surrounded by numerous police cordons, and many participants were detained and sent back.

Until the day of the formation of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, on October 18, rallies were scheduled in the places where Crimean Tatars live, but the authorities prevented them in every possible way. In response, Crimean Tatars in the cities of Bekabad, Tashkent, Krymsk (Krasnodar Territory) and Biloghirsk (Crimea) held thousands of protests against repression.

On December 24, 1987, the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a resolution on “temporary restriction of residence for people arriving” in most cities and districts of Crimea, as well as a number of cities in the Krasnodar Territory. But at the same time, an organized recruitment of workers to Crimea (about 50,000) among residents of Ukraine and russia was announced. All these measures were urgently taken to prevent hundreds and thousands of Crimean Tatar families from moving to Crimea on their own. In the Crimea, they were also not registered and were not allowed to formalize the purchase of a house.

On February 14, 1988, a rally was held in Simferopol with the participation of more than 2,000 Crimean Tatars who spoke out against the oppression of their rights. On the same day, a protest action was held in Gelendzhik (russia) with the participation of the same number of people. And a large force of police and troops on armored personnel carriers was brought to Tashkent to prevent the Crimean Tatar rally planned here, and roundups were organized in the city. From February to May 1988, Crimean Tatar rallies were held in various cities and in Moscow, some Crimean Tatars announced a protest hunger strike.

By the 44th anniversary of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people, on May 18, 1988, demonstrations were held in 22 cities of the country with the participation of more than 25 thousand Crimean Tatars. On May 26, 1988, a tent town (with 500 tents) was set up near the Crimean village of Zuya, which was completely destroyed by the forces of 2,000 soldiers and policemen.

On June 9, 1988, the state commission for solving the problems of the Crimean Tatar people issued a conclusion according to which “there are no grounds for the formation of Crimean autonomy.” The commission made it clear that the state has no intention of solving the issue of returning the people to their homeland and restoring their rights.

A wave of thousands of demonstrations and protest actions by the Crimean Tatars against the decision of the commission swept through their places of residence. On June 20, 1988, a mass strike began in the village of Nizhnyobakansky, Krasnodar Krai, in which about 5 thousand people took part. The initiative was supported in the neighboring regions and in Uzbekistan. On June 23, mourning rallies were held everywhere for the 10th anniversary of Musa Mamut’s self-immolation.

On June 26, 20 thousand demonstrations took place in Tashkent. Police and military units dispersed the protesters with rubber batons and tear gas. Several thousand people were beaten and detained. In Moscow, about 900 people who came to express their protest before the delegates of the All-Union Party Conference were beaten, detained and forcibly expelled from the city.

From the end of June to the middle of August, thousands of Crimean Tatars from different regions held a nationwide strike. More than 1,500 people were dismissed for “absenteeism”.

On July 23, 1988, to the anniversary of the publication of the TASS statement, which once again reported false and slanderous fictions about the Crimean Tatars, a day-long hunger strike was held in the Temryut district of the Krasnodar Territory (the village of Senna) with the participation of 500 people.

From April 29 to May 2, 1989, the 5th All-Union meeting of representatives of the initiative groups that founded the Organization of the Crimean Tatar National Movement (OCNM) was held in the city of Yangiul, Tashkent region. Human rights defender and national leader Mustafa Dzhemilev became the head of the OCNM.

Despite the opposition of the authorities, the pace of independent return of the Crimean Tatars to the Motherland grew. Along with the whole nation, the Crimean Tatar national movement gradually moved to Crimea.

On June 26-30, 1991, a national congress of Crimean Tatars was convened in Simferopol – II Kurultai of the Crimean Tatar people, which united most of the initiative groups and organizations of the National Movement. Kurultai delegates elected a representative body – Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, which consists of 33 people and functions on a permanent basis.

Since then, the people’s struggle has reached a new level – affirmation and self-determination in the Motherland.

Authors: Dilyara Asanova, Elvedin Chubarov.